I love the holiday season, which begins with Thanksgiving Day. When I was pastor in downtown Oakland, the congregation marked the day of thanks by offering a wonderful, complete Thanksgiving Dinner to anyone in the community who wanted to join. Homeless folks, people who did not speak English, people without family or even friends, joined the day’s gathering to sit at a table and to be served by other grateful folks. For many years, that tradition became part of my personal Thanksgiving, as I looked out at the gathered people and said to myself, again and again: “these are my people!”

And Jeff and I mark the holiday every year now by arriving at Norman and Cheryl’s cottage on a hill in San Francisco, climbing the narrow stairs to the top of a hill, our arms filled with pies – our contribution! – and to sit at the long, narrow table filled with an assortment of Bahlert-related people every year. As the day progresses and the dusk and darkness come, families with little ones begin to gather their belongings and leave, with much ado. The tiny kitchen which produced the feast we’d all enjoyed is full of helpers bumping into each other, cleaning up, continuing the dinner-time conversation. And then – just like that! – we all descend the steps and walk to our cars on the quiet streets and drive home, mentioning to one another moments from the day, who had grown, who talked to who, how much older everyone is (except for us, of course!), and probably feeling a bit of sadness that another holiday has passed.

In the Midwest, the shorter days and long evening of dark and cold have begun by this time of year. There’s a sense of “cocooning” that we don’t know in the same way here in California. And missing now, also, is the childhood sense of a quiet and light filled season, beginning with Thanksgiving, that won’t end until after Epiphany, in January.

My mother honored the season of holidays each year by hosting Thanksgiving Dinner at our upper flat, and by creating for my sister Suzie and me a holiday tradition. In the 50’s and 60’s (of the last century), the holiday season did not officially begin until Thanksgiving. On the day after Thanksgiving, my mother and Suzie and I took the 23 bus from the North Side to downtown Milwaukee, now mysteriously decorated with lights and ribbons along Wisconsin Avenue, still a booming shopping district at the time.

We’d step off the bus at 3rd and Wisconsin to walk through the Boston Store, which anchored the downtown at that time. My mother held tightly to each one of us as we walked through the crowded store, the lights and music having followed us from the street into the store.

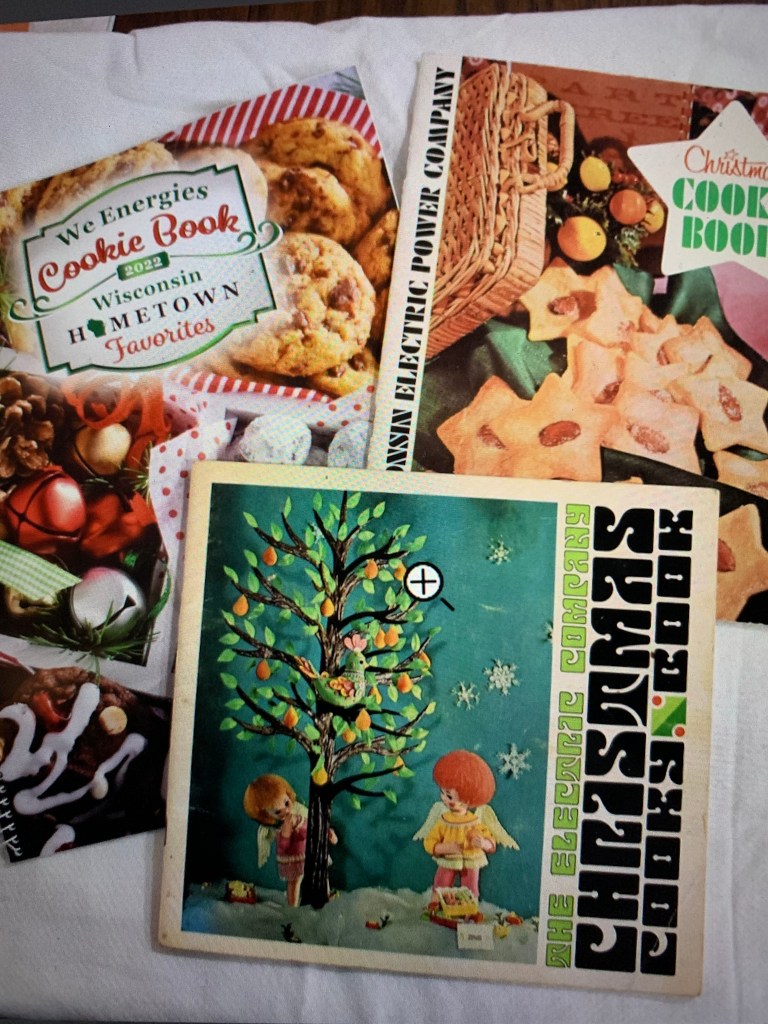

Then, we’d walk, first to the Wisconsin Electric Company, and then to the Gas Company, to take in the cookie displays at each one. My mother made sure that at each place, she was provided with 3 copies of the new cookie book published by each company each year. She loved to try new recipes, and she loved to re-create those that had been her favorites – or dad’s favorite, or mine, or Suzie’s. Unknown to me, she wrote notes as she baked: “a favorite,” “takes a bit less powdered sugar than called for,” “makes a big batch!”

I didn’t discover the notes until years later, when I had my own apartment in Green Bay, and when Mom presented me with the collection of cookbooks she’d saved, just for me.

I’m not a great baker, although the family in San Francisco allows me to bring pies as my contribution to Thanksgiving. My mother loved to bake: “that’s the fun of it,” she’d say. And I expect she envisioned some sort of future for me and for my sister, based on her own life. Neither of us grew to have quite that future, I expect; it was her dream for us, regardless. The year after I retired, I baked a few batches of cookies, looking for a new way to fashion my life after an adulthood of work, often in a “man’s world.” That’s the year I reached high onto the kitchen shelf reserved for our cookbooks, and retrieved the cookbooks Mom had saved so carefully for me. And that’s when I saw her notes, in her particular hand-writing, written with me in mind, written with the relationship between the two of us holding us together.