There was always room for a sewing machine in our upper flat. Looking back now, I see how cramped those working class houses were, their windows covered with curtains to keep out the cold of the freezing winters in the Midwest. But there was always room for Mom’s sewing machine.

Well, it was Mom’s sewing machine until Suzie and I learned to sew. Then, if I was working on an outfit with a Simplicity or McCall’s pattern, chances are that either Mom or Suzie was working on something too, and when I stepped away from the machine to get another piece of fabric, carefully looking at the directions – I’d find a spool of thread in a color that didn’t match my material already in the machine. The sewing machine was ours – the three of us.

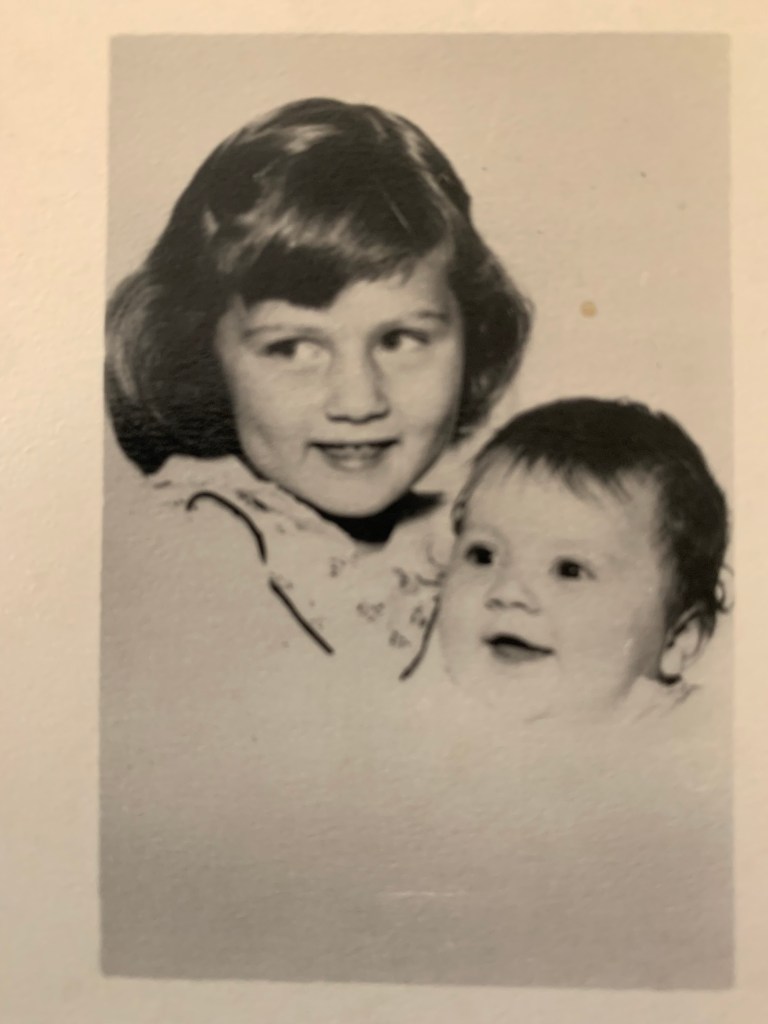

Like a lot of mothers over time, Mom was happy to have two daughters for her to make homemade clothes from the patterns. She must have worked many hours when we were at school and when Daddy was at work in the steel mill. And because she was happy to have two daughters, she was extra happy (I expect) to be able to make them matching outfits. To make us matching outfits – Suzie and me.

One Easter, Mom made Suzie and me matching dresses, including capes lined in pink fabric. She bought matching Easter hats – “in your Easter bonnet…” and Suzie and I were models, standing together on the front lawn of the flat, looking into the camera.

Mom made us matching outfits, that is, until I told her at some point that I didn’t want to be dressed like my little sister. Thankfully, Mom agreed – or at least understood – because I heard her tell the story to my Auntie Anne not long after. And so the days of matching outfits came to an end.

+

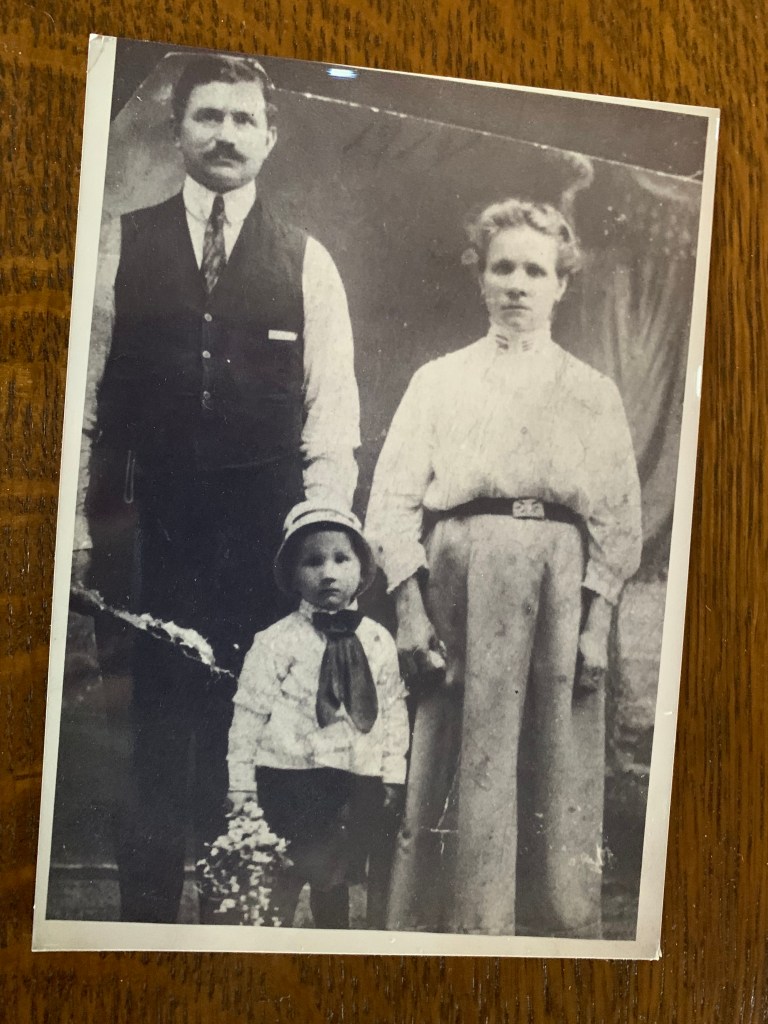

We are well into the 21st century now, and those days in the cramped flats – winter and summer, and fall and spring, when the fragrance of lilacs in the huge bushes in front yards that adorned the streets wafted down to walk with us – are well in the past. It’s interesting that some of the feelings remain, filtered through the grief at remembering all those who are gone now, and how they loved us, each in their own way. How their dreams still live in us.

And I’m grateful for my mother – coming from poverty and abuse – and how she crafted the best life she could for us, for us all. How she protected us, to the best of her ability, how she made a home for us, and how happy she must have been to sew Easter outfits for her two daughters.