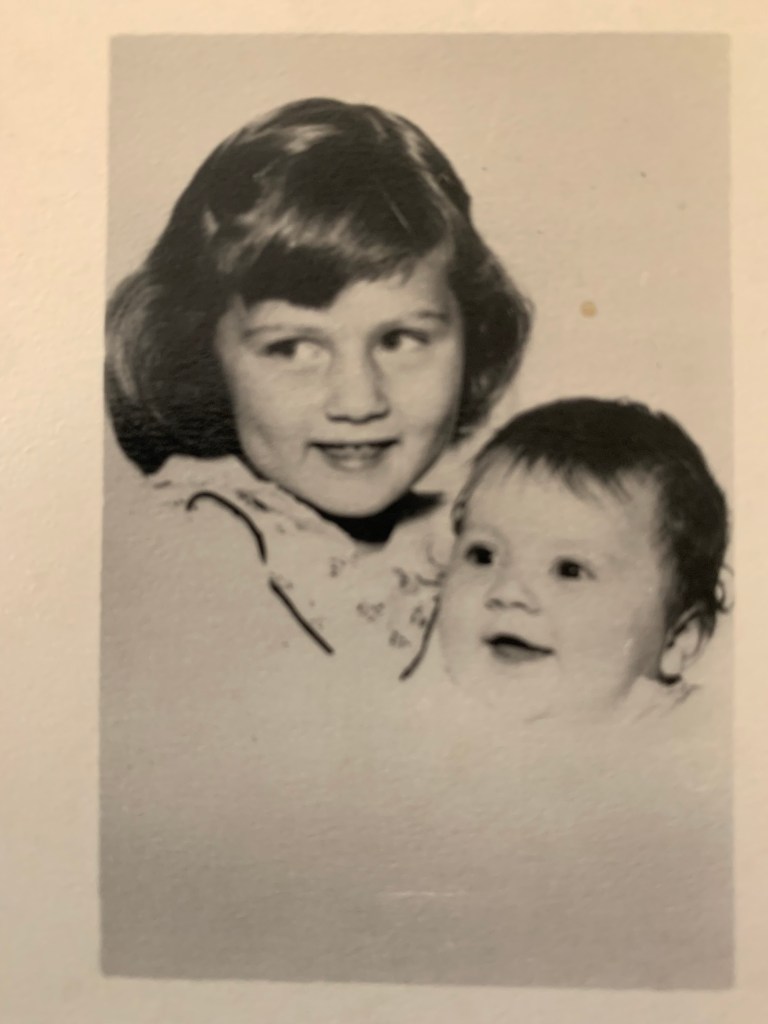

At home, I was the big sister. And so I was thrilled when my brother Ronn brought home a friendly and fun young woman – Sue – and introduced her to the family as the “girl” he was going to marry (this was the early 60’s, when young women were still referred to as “girls).” And I was thrilled when Sue, who was the middle of three sisters in her own family, took an interest in me.

Sue was the big sister I had never had. She listened to me and she made me laugh. (Sue and me laughing would play a big part in our lives as the years unfolded). I cherish a vivid memory of Sue and me together in the cramped bathroom of my family’s upper flat on the north side of Milwaukee. We sat together as she cried about an argument she was having with Ronn. More often those days, Sue made Ronn laugh, and Ronn made Sue laugh. As I bring Sue to my memory now, I can see her wide smile and the light in her eyes. She liked me, just as I liked her. And – she would never fail to tell me the truth. Never.

*

Early in their marriage, Ronn had had an accident as he drove alone on a Milwaukee street; he ended up in the hospital for several weeks. As the years unfolded, he would need to be hospitalized again and again. And so one summer, as Sue was Mom to three children under five already – David, Alicia, Vicki Sue – she was about to give birth to her fourth child. I stayed with her in their house in the suburbs of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, slept in her bed with her as she tossed and turned, unable to sleep a full night in the last days of this pregnancy. Ronn was hospitalized again.

Most nights, the two of us would sit together on the screened in porch, talking and laughing in the dark. All night long. That year, the cicadas arrived to fill the air with their loud screeching calls, early in the mornings, just before daylight. The children were still asleep, although we didn’t know when that would change, and our world was just the two of us, facing one another in the dark. Sue was a smoker – she smoked until she died in 2015 – and I listened and laughed to her deep voice as I watched the light of her cigarette go up and down in the dark, sitting there together until the morning light broke the silence that surrounded us.

*

The last time I saw Sue was in the spring of 2015. I’d taken a trip to visit the family in Northern Florida on my own that year, and the day before I left, I went to lunch with Sue and Alicia, her older daughter, who was her caregiver. It seems that a medication that Sue was taking was also taking her memory, and from time to time, she’d stare at me quizzically, trying to recall who I was. Then, at one point in the conversation, a moment of clarity, she said to me: “you’re a minister.” Yes! She did know who I was.

After lunch, I drove Sue and Alicia back home. I got out of the car to give them each a hug, and Sue held on to me for a long time. As I drove away a few moments later, I watched in the rear view mirror as Sue stood, waving and waving.

*

“Sue, Sister, Sweet”

I remember when I first knew you were my sister –

you, sitting on the edge of the claw footed bathtub

in the crowded bathroom of an old Milwaukee flat, crying.

I listened to your tears, and then, I knew:

You are my sister, Sue.

I remember you, 8 months pregnant – again (!)

I remember your voice all night long

in the dark Carolina night,

the light from your cigarette, up and down, up and down,

the two of us, laughing, laughing:

We laughed until dawn.

During the day, you were Mom.

Years later (in my new life)

you brought me a home-baked goodie

while I was still in bed – insisting that I accept this gift of love!

I remember you marching me to the classical music CD’s in the back

of Barnes and Noble:

You bought me Beethoven.

I listened, all spring long, to the minor notes,

mourning another Sue.

Now, these notes, this mourning, is for you.

I mourn for you.

I remember – I will remember always –

you waving goodbye (I watched you in the rear-view mirror),

as I drove away from you – for the last time.

“I don’t know when I’ll see you again, Sue,” I said into your silence.

You knew, you knew, you knew, my sweet, sweet sister, Sue. (poem by meb, 2015)